PREVIEW

As China slows down and the US dollar strengthens, will African governments try to diversify and industrialise their economies?

Africa, with its 1.2 billion people, will again be the continent that achieves the fastest economic growth this year but its monied cheerleaders will have pause for thought as some harsh realities hit home. The six biggest economies – Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa – all face their own political demons. These range from insurgencies, worsening corruption and youth unemployment to messy successions and national elections.

Asia, with its 4.4 billion people, will grow the second-fastest, slowed by another year of poor growth in Japan and sweeping internal adjustments or rebalancing in its biggest economy, China. These two developments are related. Increasingly, Africa's economic growth is fuelled by the development of domestic production and consumption, as well as its commodity exports to the hyper-economies of China and India.

So the big question for Africa's economic managers is, to what extent can national and regional trade and production make up for Asia's faltering demand for Africa's commodity exports? Behind that calculation is the search for investment to finance Africa's growing need for the power stations, roads, ports and telecommunications to enable it to build on its economic momentum.

Almost every African economy is held back by a lack of electric power (AC Vol 56 No 2, Planning puts power first). Even the combined power investment plans of the African Development Bank, the World Bank, the China Development Bank, and the United States government's Power Africa programme barely meet a quarter of current demand. Africa's requirement for infrastructure finance is reckoned at over $90 billion a year, of which about $25 bn. will be raised internally.

Another global development affecting Africa's economies in 2015 will be the strengthening of the US dollar and higher US interest rates. That will deter some investors from going into Africa because the US market can offer them safer, if less lucrative, investments. Other financiers will look at the slowing demand for minerals and lower oil prices and cut back on investment plans in Africa's natural resources. More imaginative entrepreneurs, inside and outside Africa, will see the longer-term potential of industries such as renewable energy (especially solar, wind and hydropower), farming, fisheries, fashion and textiles, culture and communications. However, overall, African states will struggle harder to raise investment dollars this year, even from their big trading partners in Asia.

Testing China

The Sixth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, the first to be held in South Africa, will be a key test of Beijing's foreign commitments as it tries to boost consumption at home and manage the massive internal migration from China's hinterland to its more prosperous coastal zones.

There is another international marker this year of critical importance to Africa, according to demographers at the United Nations: the working-age population (16-64 years) will reach an historical peak of 66% of global population. New research points to a stagnation and eventual decline of world population in the second half of the 21st century. Expect to see concern about a population explosion change to worries about a population decline. The question faced by the big developing economies – China, India, Brazil and Indonesia – is whether can they get rich before they get old. Africa, the world's youngest continent with the highest average birth rate, could reap the demographic dividend – as China did – by using the boom in its working-age population to boost economic production and exports.

New ideas about off-grid electricity and solar power offer more opportunities to leapfrog current constraints on energy. African delegates to the climate change summit in Paris in December are to argue for greater investment in the continent's renewable energy resources. They will also be looking for more serious international finance to mitigate the effects – desertification in some areas and flooding and extreme weather in others – of global warming.

Both the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have revised downwards their forecasts for Africa's economic growth this year due to increasing economic and political risks. Internally this includes: the direct effects of the Ebola outbreak on Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone and its consequences for the region (although earlier calculations of losses of US$30 bn. have now been reduced to under $10 bn.); pressure on government budgets from increased demand for state spending; the conflicts in South Sudan, Sudan and Central African Republic are causing a humanitarian disaster as well as disrupting regional trade, while the Boko Haram insurgency in north-east Nigeria is affecting its neighbours, Chad, Cameroon and Niger in the same way.

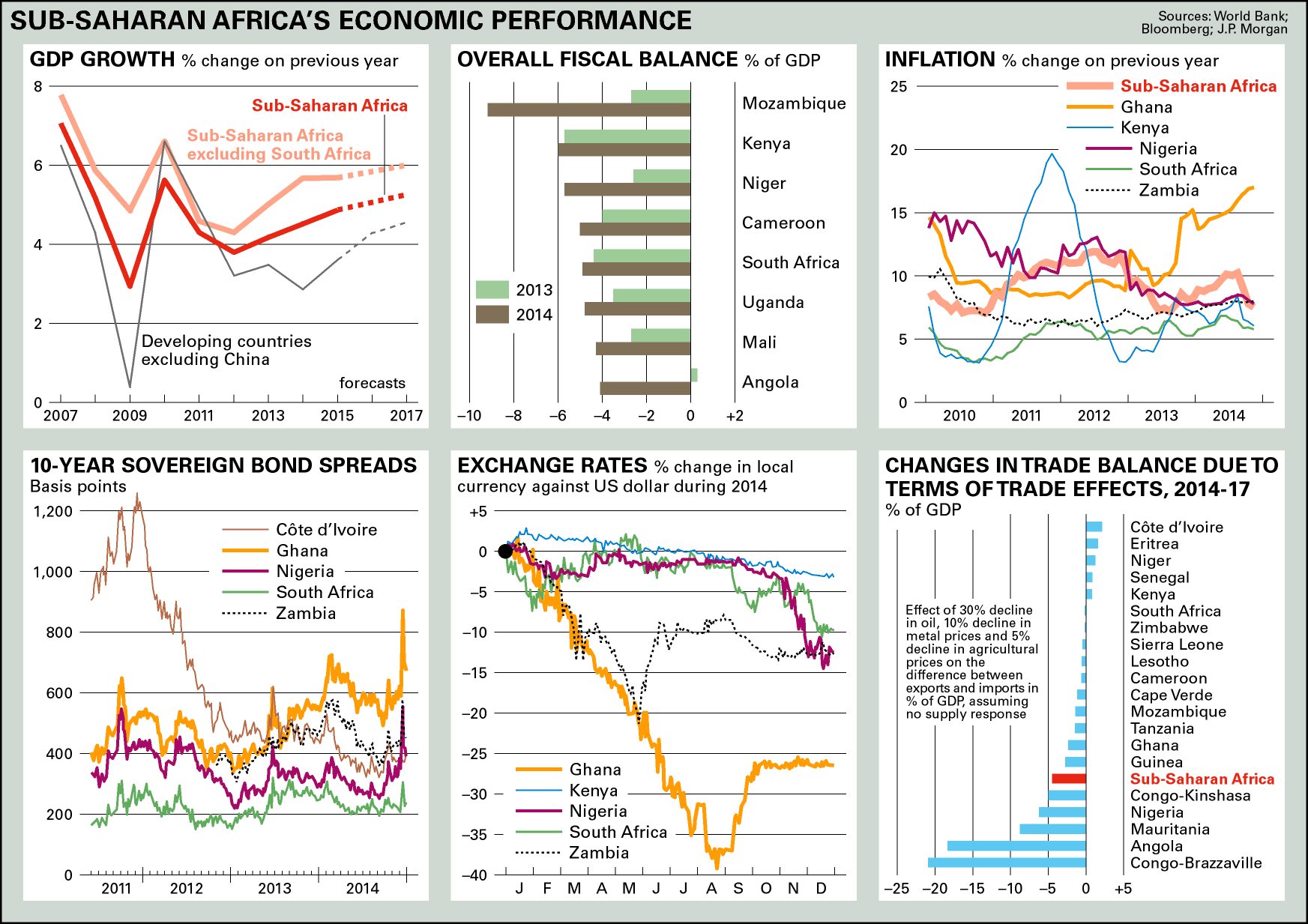

The external risks for Africa are a re-emergence of volatility in international financial markets that would hit portfolio investments – such as shares and treasury bills – in South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria and Zambia among others. However, the biggest international factor would be a worse than expected slowdown in the key markets for African commodity exports – China, India, Brazil and the European Union. So far, metal prices are down by 10% and agricultural commodities by 5%: further prices falls would hit countries such as Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Tanzania and Zambia.

Such falls are likely to be short term. After the US financial crisis in 2008, Chinese manufacturers cut their commodity imports sharply and then worked through their inventories. Two years later, they came back into the market to stock up again at bargain prices. However, many of China's trade and investment deals in Africa are premised on much longer term arrangements that guarantee resource supplies to China and some predictability for African exporters.

Yet there are some bumps in the road over the next few months. In January, the IMF reduced its 2015 growth projections for gross domestic product for the Eurozone and China, among others, and forecast overall global growth of 3.5%. Its projection for Sub-Saharan Africa fell to 4.9% (AC Vol 56 No 1). This compares unfavourably with the figure of over 5.7% predicted in Ocober in the IMF's Sub-Saharan Africa Regional Economic Outlook. Among key African economies, the IMF has specifically revised downwards South Africa's anaemic growth projections to just over 2% and Nigeria's from over 7% to less than 5%. The World Bank now expects regional growth of 4.6% in 2015, increasing to over 5% by 2017. Ecobank, Africa's biggest regional bank, predicts growth of under 5% (AC Vol 55 No 6, Ecobank's next act).

The divergent fortunes of Africa's economies raise questions about the underlying growth story – the importance of government fiscal and monetary policy, investor sentiment, growth driven by local production and consumption and vulnerability to external pressures and markets. After last year's GDP rebasing, Nigeria overtook South Africa as Africa's largest economy (AC Vol 55 No 1, Economy billowing, politics floundering).

The fall in international oil prices, dipping under $50 a barrel, again exposed Nigeria's dependence on oil revenue. The government was forced to cut its 2015 federal budget: its budget projections are based on a benchmark oil price, which has been revised down from $77.5 a barrel in 2014 to $73 and now to $65 – but this is still $10-15 a barrel higher than market realities. Critics of President Goodluck Jonathan's governing People's Democratic Party (PDP) and his Finance Minister, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, have called for the benchmark to be cut further. This comes as the government is reeling from the devaluation of the naira, the rise in interest rates and other monetary tightening. Overall foreign exchange reserves (at just over $34 billion) and savings in the Excess Crude Account (now just down to $2 bn. from over $4 bn. in December) have fallen sharply over the last year.

The war waged by Boko Haram, mainly in the north-east, has killed more than 10,000 people over the past three years. Moody's, the ratings agency, recently said that the insurgency was hitting Nigeria's sovereign debt rating and discouraging investors, as well as damaging business confidence. Some investors worry about the Central Bank of Nigeria hindering their efforts to repatriate foreign exchange earnings but confidence in underlying, long-term growth is still strong.

The African Development Bank Country Director, Guinea's former Finance Minister Ousmane Doré, argues that Nigeria's growth is increasingly driven by domestic, non-oil factors, reflecting the official AfDB view that the agriculture, services and other non-oil sectors are strong (AC Vol 52 No 24, Storm warning). This view is partially supported by the GDP rebasing or recalculation, which showed a significantly lower oil-sector contribution to GDP – and higher services contribution – than previously. Doré believes that the Finance Ministry and government in general have made great efforts to adjust to the reduction of oil revenue which, despite the home-grown oil theft or illegal bunkering and vandalism losses, is driven by factors largely outside their control.

The Africa Economist at Citi (formerly Citibank), David Cowan, also takes a longer-term view. He suggests that Nigeria's ability to devalue its currency, unlike Africa's CFA franc-zone countries, should allow it to absorb the oil-price shock, with a further devaluation likely after this month's elections. While Cowan, like others, acknowledges the oil-related risks to Nigeria's banking sector, he believes that the low exposure of the banks to exchange rates vastly reduces the likelihood of another banking crisis and that government attempts to reform and invest in the power sector could, if successful, provide significant growth.

The Ebola effect

The Ebola-affected economies of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone will experience economic drag. Perhaps West Africa's most disappointing economic story is that of former economic star Ghana, which faces a moment of truth this year.

Ghana's ability to raise external finance and pay for its ambitious development plans now depends on agreement on an IMF adjustment programme. Should the cavalry not arrive, its will also face difficulties in the second half of 2015 in rolling over foreign and local debt obligations. The World Bank projects Ghana's 2015 growth at just under the Sub-Saharan average.

In 2014, not only did yields on Ghana's Eurobond rise above levels in other African countries, the cedi also performed poorly against the dollar. Ghana's Finance Minister, Seth Terkper, who has grudgingly accepted the criticism of ratings agencies that have downgraded Ghana, has failed to reduce the massive public sector wage bill. Despite the recent progress of the delayed Western Region gas project to fuel power stations, electricity shortages still hold back growth.

A brighter outlook for the main East African economies this year points to their more diversified economies. Oil prices help explain some of this. Late last year, when oil prices were slightly higher, Ecobank projected a cut in GDP growth among 'middle Africa' oil exporters. This contrasts with lower oil prices acting as a 'tax rebate' in oil-importing countries – increasing people's disposable income, helping investors and businesses, and improving importers' fiscal balances. This tallies with the World Bank's belief that importers in developing countries will benefit. Some economists argue that low oil prices could act as a global stimulus.

Even the pressure on Kenya's current account – from major investment projects (such as the Standard Gauge Railway from Nairobi to Mombasa) and the threat of lower tea prices, reduced tourism revenue, and the impact of any drought on Tanzanian agriculture and Kenyan hydroelectric supply – will not detract from East Africa's underlying strengths, according to Angus Downie of Ecobank.

The World Bank expects Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda to grow at 6% or more during 2015, with Tanzanian growth even exceeding 7%. In addition, Chinese and other Asian demand for East African tourism and for commodities such as coffee should still remain strong.

For oil and gas, despite the lag before commercial production begins, they will still improve the region's longer-term outlook – so long as policymakers learn from Nigeria's past woes and from Ghana's mistakes and delays on its oil and gas.

Further south, Mozambique is set to profit from a future hydrocarbon dividend. Its economy is predicted to grow at around 8% this year, albeit with a heavy current account deficit due to imports for major capital and energy projects. Yet the expectations of the governing Frente de Libertação de Moçambique threaten to out-run the revenue, which could be delayed because of infrastructural bottlenecks and poor governance (AC Vol 55 No 25, Gas regime is getting there).

In Zambia, concern over a high fiscal deficit echoes that in Ghana. Zambia is also vulnerable to fluctuating or falling metal prices, as are Mozambique and Tanzania. While the advantages of cheaper oil imports should offset lower copper export prices, Zambia's new mining tax regime worries the big mining houses, says Standard Bank's Stephen Bailey-Smith.

The IMF, which Zambia approached for finance last year, called on Lusaka in December to review plans to raise mining taxes and address the backlog of value added tax refunds to mining companies. New President Edgar Lungu, having won votes on a more populist programme, is struggling with the conflicting demands of the electorate and big business. Zambia should exceed 6% GDP growth this year.

Balance

South Africa, the continent's second largest and most advanced economy, will also gain from lower oil prices. Yet projected growth of just over 2% is only a slight increase on 2014, all the more disappointing given the country's regional significance. As David Cowan observes, though, weakness in the rand can assist exports, both within and without Africa. On the downside, as Renaissance Capital's Thabi Leoka says, gains from lower oil prices and fuel costs could be counter-balanced by further rises in electricity prices at a time of disruptive load shedding (AC Vol 55 No 25, The politics of power). But businesses have to invest in private power generators and the manufacturing and mining sectors could be hit again by strikes.

After recent political turmoil, some North African economies are turning the corner. While set to grow more slowly than Sub-Saharan countries or Africa as a whole, with expected growth of over 3%, Egypt appears to be on an upwards path, as is faster-growing Morocco. In both, manufacturing is growing significantly – unlike countries south of the Sahara.

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2024

https://www.africa-confidential.com:1070

Prepared for Free Article on 22/11/2024 at 19:04. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.