PREVIEW

As the rival leaders appear indifferent to the slaughter and threats to stability, support is growing for a serious intervention force and targeted sanctions

The pressures of war are mounting but President Salva Kiir Mayardit still sports a black ten-gallon hat and a hefty walking stick. Looking tired and stooped, Salva hectored a group of African leaders and security experts on 27 April on the justice of his cause. He and his allies in Juba had no choice but to resist a 'desperate' and 'fully armed' rebellion, he said, questioning why foreign governments and international organisations were so sluggish in their support for an elected government.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, Sudanese President Omer Hassan Ahmed el Beshir and Nigerian ex-President Olusegun Obasanjo nodded sympathetically as Lieutenant General Salva addressed the Tana Security Forum last week in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. The ostensible subject was illicit financial flows – of particular relevance to South Sudan, where the argument over the spoils of the oil industry helped to trigger the conflict.

The war in South Sudan has become Africa's bloodiest and most intractable conflict this year. Hundreds more civilians have been slaughtered over the past month, adding to a death toll in the tens of thousands; over a million of the country's six million people have fled their homes and farms, and now widespread famine looms. Ethiopia's grand economic plans need regional stability above all. More immediately, the cash-strapped regime in Khartoum desperately needs to keep South Sudan's oil flowing and to collect transit fees as it is piped to Port Sudan. Obasanjo has close ties with South Sudan: he chairs the African Union investigation into the violence in Juba on 15 December which marked the start of the violence (AC Vol 55 No 1, From power struggle to uprising).

As Salva Kiir and his delegation left the seminar, Obasanjo called them back with a simple message: if the leaders of South Sudan could find a way to make peace with Khartoum after half a century of warfare, how could they not reach an agreement between themselves. Gripping him in a bear hug, Obasanjo told him: 'The buck stops with you Mr President.'

Over 1,000 kilometres to the south-west, Salva's rival, Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon, was hosting a delegation of senior African and European officials at his redoubt near Nasir, in Upper Nile State and site of his split from Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) leader John Garang de Mabior in 1991 (AC Vol 46 No 21, Gunmen or soldiers). Led by Ethiopia's former Foreign Minister, Seyoum Mesfin, and South Africa's Cyril Ramaphosa, the officials urged Riek to respect January's truce and rein in his forces, and their allies such as the White Army. Ramaphosa spelt out African concern at the human cost of the devastating war and the wider damage to the region's development.

Legal scrutiny

Navi Pillay, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, and Adama Dieng, the UN Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide, delivered a tougher message about the responsibility of both Riek and Salva for the worsening human crisis in their country. They told both leaders that they and their commanders were under legal scrutiny, with regard to claims of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

UN investigators have already found three mass graves, one in Juba (in a government-controlled area) and two in Unity State, where Riek's forces hold sway. Both sides are accused of targeting civilians and soldiers by ethnic identity. A senior Western military official in the region described the crisis in South Sudan as Africa's worst for more than a decade.

After the meetings, Pillay said both leaders had 'embarked on a personal power struggle that has brought their people to the verge of catastrophe.' The UN warns that unless local farmers are able to plant crops before the rainy season takes hold, South Sudan faces a famine worse than any since Ethiopia's in the mid-1980s. Pillay said responsibility for such a catastrophe would 'lie squarely with the country's leaders, who agreed to a cessation of hostilities in January and then failed to observe it themselves, while placing all the blame on each other.'

A week earlier, in a rare moment of consensus the UN Security Council announced it was considering sanctions on both parties. The French Ambassador to the UN, Gérard Araud, also spoke of plans to toughen the mandate of the UN Mission in South Sudan before it comes up for renewal in July. When fighting erupted in December, the Council approved a plan to double the size of UNMISS to 12,500 troops but it is still some 3,000 under strength. On his arrival in Addis Ababa on 30 April, the United States Secretary of State, John Kerry, added his weight to calls for a regional force to stop the fighting but did not offer specific military assistance.

Ethiopia's Mesfin, who is the lead mediator in the military and political talks between the South Sudan government and Riek Machar's SPLM in Opposition, said the configuration of forces was still under discussion. Western officials are backing plans by the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development to send three battalions (about 2,000 troops) to protect its ceasefire monitors in the field, which would also come under the joint authority of the UN, IGAD and the AU.

As pressure mounts, the two sides resumed political talks in Addis Ababa on 28 April, initially through Mesfin as mediator. Showing some frustration at the slow pace of progress, Mesfin said the time for 'talks about talks' was over and there would have to be serious negotiations about an interim government in Juba. Yet who would be in that government, let alone who would head it, remain points of high contention, as both sides have become progressively more polarised.

That is why many inside and outside the country support the calls for a face-to-face meeting between Salva and Riek to tackle both security and political issues. The immediate obstacle to that is the Juba government's treason charges against the three leaders of the SPLM in Opposition who are running the rebellion: Riek, General Alfred Ladu Gore and Taban Deng Gai, who leads Riek's delegation in Addis Ababa.

However, Juba has already released eleven dissidents it had charged with treason. The last four, freed on 25 April are: Ezekiel Lol Gatkuoth, Majak d'Agot Atem, Pa'gan Amum Okiech and Oyay Deng Ajak (AC Vol 55 No 6, Talks or treason trials). On the previous day, Justice Minister Paulino Wanawilla Unango had withdrawn charges against the Group of Four (G-4) and the seven freed earlier (G-7), citing lack of evidence (AC Vol 55 No 3, A deal under duress).

Bridges and guns

There are hopes, especially in the international community, that these eleven, who are critics of Salva's government but oppose the military rebellion, could be a bridge between the two sides. Many South Sudanese blame the former ministers for the current crisis, while militants such as Puot Kang Chol, who chairs the SPLM Youth League on Riek's side, strongly oppose their inclusion. 'If you don't have a gun, how can you get a place at the table?' he told Africa Confidential.

However, John Luk Jok, the Spokesman of the G-7, said it was asked to stay on for further meetings in Ethiopia after the internal talks about the future of the governing SPLM ended on 26 April. John Luk told AC that his group hoped to join the talks between Salva's government and the SPLM in Opposition, presided over by IGAD. 'It's the Group of Eleven now. We hope the four will be able to travel and unite the group'.

Last month's massacres in Bentiu and Bor have reinforced the urgency of the security and political initiatives. The Uganda Peoples' Defence Forces are assisting the government army, the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) against Riek's fighters. The UPDF had promised to withdraw by the end of April but changed its mind because IGAD has not sent in its own force. 'If Uganda left in the absence of another force to fill the vacuum, at the very least you would have a Central African Republic situation,' said Uganda's Chief of Defence Forces, Gen. Katumba Wamala. Many believe that without Uganda's backing, Juba would be vulnerable to a takeover by Riek's forces.

Forces supporting Riek took Bentiu again in the first week of April: when government reinforcements failed to arrive in time, the SPLA used its old guerrilla tactic of withdrawing. The rebels committed atrocities on an epic scale, according to locals and UN officials. Non-Nuer people were targeted and hundreds of civilians were slaughtered, many inside the hospital, a Catholic church and a mosque. The rebels also massacred dozens of Sudanese, many of them refugees from Darfur.

So when displaced Nuer who had sought sanctuary in the UNMISS camp in Bor celebrated these attacks, trouble loomed in the mainly Dinka town. Amid the singing and dancing, one song renamed Bor 'Ngundeng City', after the legendary Nuer Prophet Ngundeng Bong of the 1830s, whose father, Bong Can, died fighting the Dinka. 'This was the ultimate insult to the young men of Bor,' observed one Dinka source.

On 17 April, a mob of about 350 youths headed for the (Nuer) Governor's house but he was out. All Nuer officials have since left town. They continued to the UN camp, where they produced copious weapons along with wire-cutters, plus mattresses and blankets to throw over the perimeter razor wire. They were soon inside, attacking not only Nuer people but UN staff and anyone else in their path.

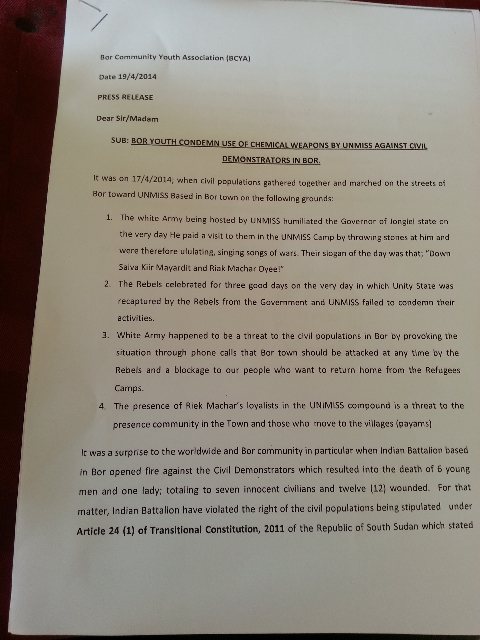

They killed at least 40 people but the UPDF, which has its forward base at Bor, claimed the credit for stabilising the situation. On the day after the assault on UNMISS, a well-written leaflet from the Bor Community Youth Association circulated, suggesting some serious organisation, perhaps at a senior level, behind the attack. Headed 'Bor Youth condemn use of chemical weapons by UNMISS against civil demonstrators in Bor', it claimed that fighters from the White Army, who support Riek, were being sheltered in the camp and had stoned the visiting State Governor. It also claimed that Indian soldiers from UMISS had used chemical weapons against the attackers: it seems they initially fired tear gas cannisters before using live ammunition and shot six people dead. At least one of the casualties wore a police uniform, raising more questions about the identity of the attackers.

Hard-to-control youth

The Juba government has been mobilising and arming Dinka youths across Bor and Twic East. 'The cattle camp youth are a much more serious military opponent to the White Army than the SPLA, despite all their nice new shiny weaponry', commented a Western source. The White Army is the hard-to-control, youthful Nuer militia that does much of the fighting on Riek's side. The SPLA, which is having trouble recruiting young men from other areas, may have decided that 'self-defence' militia are the best option adjoining Riek's areas.

This is an old tactic, used in the 1990s to fight invading Northern Sudanese militia, especially in Bahr el Ghazal. The then SPLM/A leader, the late Col. John Garang, who was fully trained in conventional warfare and also a Bor Dinka, was cautious about the tactic even then, well aware that it can fuel intra-clan fighting and traditional cattle raiding. That is happening now among the Agar Dinka in Lakes State and also in Warrap.

The angry young men who form the basis of most militia worldwide have an extra motivation to fight in Bor. They are the descendants and, in some cases the survivors, of the Bor Massacre of 1991, when Riek's forces killed over 2,000 Bor Dinka during his first split from the SPLM/A. Many returned in 2005, the year of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, from their refuge in Western Equatoria and they have not forgotten.

Questions persist about SPLA capability. There is a danger that the sacking of the Nuer Chief of Staff, Gen. James Hoth Mai, on 23 April fuels Nuer-Dinka polarisation, not least because his successor, Lt. Col. Paul Malong Awan, has long been seen as a leader of Salva Kiir's Dinka homeboys from Bahr el Ghazal, where he was previously State Governor. Hoth was widely praised for keeping most Nuer troops loyal to the SPLA and for steering a low-profile and anti-inflammatory course during the crisis.

As relatives and neighbours were killed, this took its toll and commanders began to complain that his mind was not on his job, say South Sudanese sources. His military acumen was already in doubt, said a Western military source, mentioning the Jonglei conflict between the (temporarily) reformed Nuer rebel Peter Gatdet Yaka and the Murle ethnic militia: 'Whoever makes a recent traitor into a Divisional Commander and sets him against an agile youth movement: Gatdet versus Murle? Of course it was a disastrous failure.'

During the long second war, 1983-2005, Malong earned a high reputation fighting Khartoum's Murahileen raiders in Northern Bahr el Ghazal and was close to Garang. Yet he was also a maverick, well known for 'amassing wives and cattle', said a local source, whom the Chairman treated with some caution. SPLA morale rose with his appointment, we hear, but whether that applies to all Nuer troops remains to be seen. He trained Salva's personal guard and some blame him for the killings in Juba which prompted the current conflict.

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2024

https://www.africa-confidential.com:1070

Prepared for Free Article on 22/11/2024 at 19:12. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.