PREVIEW

Sprawling conflicts in 13 conflict-wracked countries are dragging down indices for social progress, economic growth and stability. The second of our special forecast editions focuses on security

Out of 1.2 billion people and 54 countries, the security crises afflicting over 25 million people in 13 countries are having a disproportionate effect on the continent's fortunes as its leaders prepare to launch the African Continental Free Trade Area in July and make good on pledges to outlaw the trade in small arms. Yet the ambition to establish a single market across Africa has not been accompanied by parallel efforts to help the movement of labour to faster growing economic regions.

'That is a political project,' a senior official at the African Development bank told Africa Confidential, 'and we have learned from the failures in Europe with regard to those issues. Economic – but definitely not political – integration is the aim.' But it is hard to separate the two.

A civil war cuts a country's economic growth by at least 2 percentage points a year, and that of neighbouring states by at least 0.5%, according to World Bank studies of conflict zones. Far beyond their geographic boundaries and local political interests, civil conflicts are unpicking societies at a time when governments want to raise capital for mega-investments in roads, railways and ports.

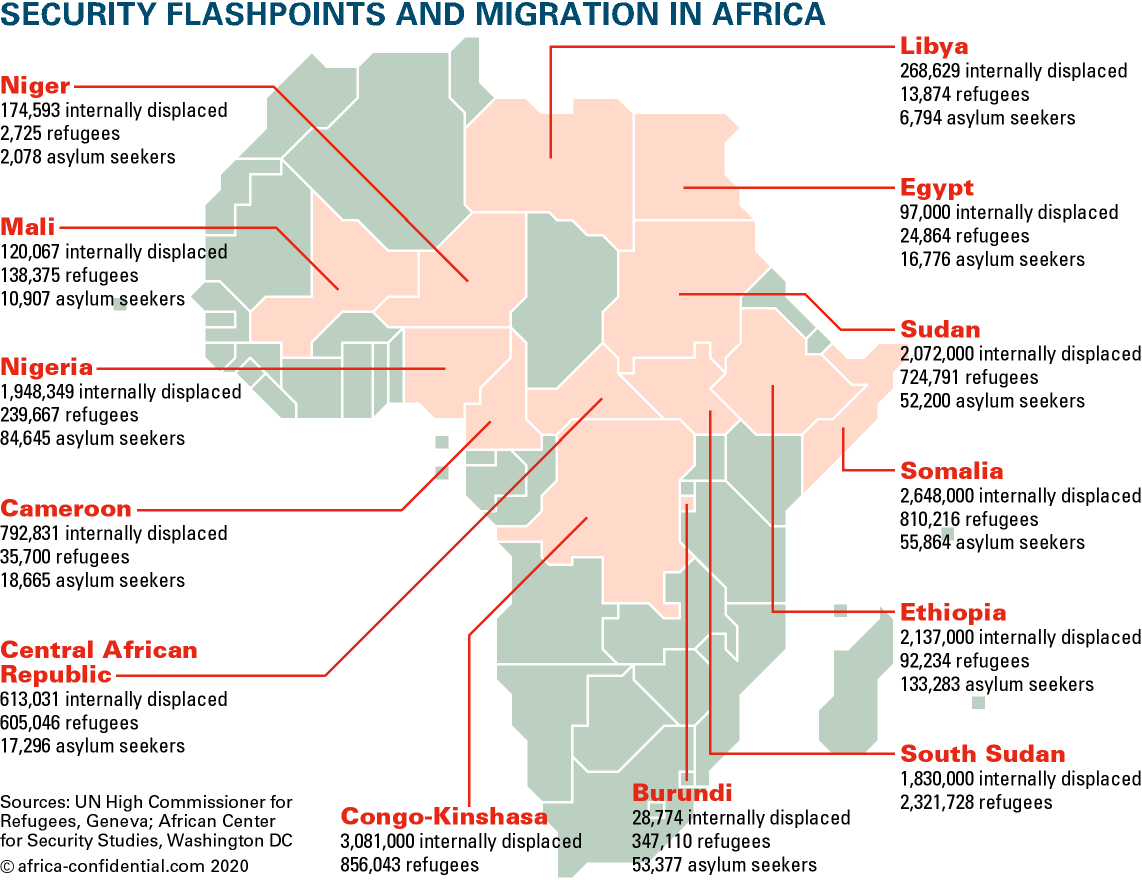

Many of the confrontations are outgrowths of unresolved conflicts, festering for a decade or more. For example, the latest wave of conflicts sweeping the Sahel (see map and analysis, Security flashpoints and migration in Africa) have their genesis in the nationalist and Islamist insurgencies launched against Mali's civilian government in 2012. In neighbouring Burkina Faso, local preacher Ibrahim Malam Dicko's Ansar ul Islam militia launched a spate of attacks three years ago in the north of the country (AC Vol 58 No 6, More progress, less movement).

Dicko was killed by Burkinabè security forces but his militia has spread its Islamist insurgency across much of the north and the east. Today there are grave concerns about President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré's ability to rein in, let alone defeat, Dicko's successors.

It is the incline of those trend lines that most trouble defence and security officers across Africa. Each year since 2014, on average over 1.4 million Africans have been forced from their homes.

Smuggling people

Over 60% of these people stay within their own country and over 95% stay on the continent. Despite those figures, European governments, particularly Britain, France and Germany, premise much of their effort to boost regional security – in the Horn, the Sahel and Libya – on the imperative of cutting migration (AC Vol 59 No 22, Don't call them transit camps). That said, the involvement of transnational crime syndicates in people-smuggling is further undermining state structures and efforts to strengthen governance.

Commercial incentives drive the people-smuggling operations across the Sahara, reckoned by European Union monitors to be earning the syndicates over US$750 million a year. Like gold-smuggling in the Sahel – reckoned to be worth over a billion dollars a year by Reuters news agency – much of the profit from people-smuggling ends up in the hands of Islamist or nationalist insurgent groups. It reinforces this vicious circle.

The African Security Center, based in Washington DC, argues that the displaced persons' crisis, the by-product of so many of the civil conflicts, has the capacity to do the most social and economic damage. Together with the climate crisis, galloping desertification and deforestation, more devastating flooding, landslides and failing soil fertility are forcing tens, often hundreds, of thousands of people across countries out of their homes and putting unbearable pressure on arable land and scarce resources.

Over the next decade, the predicted rising ocean levels on Africa's coastline, where some of its biggest and most prosperous cities are located, could force another wave of displacement. This is all happening as multilateral initiatives are faltering – whether the lacklustre climate negotiations in Madrid last year or the desperate efforts in Berlin on 19 January to broker a ceasefire in Libya.

Another complexity, evident in Libya, is the array of international interests now trying to impose themselves in Africa, picking sides in national conflicts (AC Vol 60 No 16, Proxies battle over Tripoli). The European Union is trying to counter the weakening of multilateral efforts to limit, if not end, such regional conflicts. The most serious tests of those efforts this year will be in North Africa and the Sahel where without bigger and wider-range commitments, success looks unlikely.

Security flashpoints and migration in Africa

Five sprawling conflicts and crises – in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan – have forced over 10 million people to flee their homes. Of the over 70 million displaced people across the world, according to the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, over a third are in Africa.

Somalia, where the start of the conflict dates back to the 1991 overthrow of the Siad Barre regime and multiple foreign interventions, has the highest number of displaced people in Africa. Initially fuelled by clan rivalries, Al Shabaab's Islamist insurgency has extended the conflict in high population areas and in neighbouring Kenya.

To the north in Ethiopia, the drivers of the communal conflicts are more complex still, as the local agencies try to cope with over 2 million internally displaced people. Fluctuating reports about the numbers affected show the volatility in the Oromo region and the Ogaden, which borders Somalia. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed's liberalisation moves, such as the freeing of political prisoners and allowing exiles to return, have been accompanied by a growth of ethno-nationalism. Seeing their interests threatened, local potentates are using militias to counter opponents.

South Sudan's people are scattered within its borders and in large parts of Uganda as they flee civil war perpetuated by rival and equally ruthless military leaders mobilising on primarily ethnic grounds. Congo-Kinshasa's history of national political competition backed by neighbouring states seeking part of the country's resource patrimony has displaced over 3 million and caused nearly a further 900,000 to leave the nation.

There is a growing focus on west Africa, where the authorities in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso and Nigeria suffer from rampaging Islamist militias. A deepening crisis has pitted secessionists in western Cameroon against President Paul Biya's dysfunctional regime, putting Nigeria at the centre of a threatening system of conflicts. It was 50 years ago this month that Nigeria ended its first civil war.

|

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2024

https://www.africa-confidential.com:1070

Prepared for Free Article on 26/11/2024 at 05:02. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.