PREVIEW

As the Bank celebrates its half century at a meeting in Kigali, leaders speak frankly about security and the jobs crisis

These are heady times for the African Development Bank. Against a background of resurgent economic growth, the AfDB started to celebrate its 50th birthday at its Annual Meeting in Rwanda on 19-23 May. The celebration attracted a galaxy of African political and business leaders for some unexpectedly forthright discussions about the state of the continent. Over the next few months, the Bank returns to its ancestral seat in Côte d'Ivoire, which it left a decade ago, at the height of the civil war. Over that time, many African economies have doubled or tripled in size, thanks to better national management, a huge boost in trade with Asia and investment by Western companies. That upturn in capital inflows raises questions about the future of the AfDB and other multilateral financial institutions.

As more African countries graduate to middle-income status and build their own ties with the rising economies of Asia and South America, there is less for multilateral banks to do. That is the view of many experts at the World Bank, currently going through its own turbulent reorganisation. The lack of top African economists in the World Bank's restructuring prompted a strong critique from its African governors and a half-hearted response from its President, Jim Yong Kim (AC Vol 53 No 21, Changing tribal customs on J Street).

Disillusionment with the Washington-based Bretton Woods institutions, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, is prompting their African and Asian shareholders to look more to their own regional organisations and using private capital. That makes the role of the AfDB, whose private sector unit accounts for about a third of its operations, still more important. The departure next May of Donald Kaberuka, one of the AfDB's best Presidents, is concentrating minds. As Finance Minister, he steered Rwanda's remarkable economic recovery after the genocide of 1994, and he is celebrated for his plain-speaking and hyperactivity (AC interview online, May 2007). In the past, AfDB chiefs have been criticised for being either too concerned with 'the vision thing' or unable to escape the accountant's mindset.

In his first five-year term, Kaberuka convinced shareholders that he could do both vision and double-entry bookkeeping. His dynamism attracted a new generation of African economists and development experts to the Bank's temporary headquarters in Tunisia. The second term has been tougher: the Bank shovelled money out to African states to counter the effects of the global economic crisis in 2009. International institutions and companies are picking up many of the continent's brightest talents with stratospheric salaries.

Mid-life crisis

Some staff worry about a mid-life crisis at the Bank: they cite concerns about financial controls, not least the cost of moving 5,000 people (employees and their families) from Tunis to Abidjan this year, together with a revival of in-house politicking about jobs and pecking orders, which has been largely missing during the Kaberuka era. A raft of would be presidents are already throwing their hats into the ring for next year's election (see Box, Succession scramble). As the Bank hosted its meeting in Rwanda 20 years after the genocide, Kaberuka argued that Rwanda's economic recovery showed the value of multilateral support, good policy and determined leadership. Yet at a series of seminars about leadership and governance, he lamented, 'in the light of events in South Sudan and the Central African Republic, we must sometimes wonder whether lessons have been fully learnt'. Amidst several discussions on security, political risk and governance, he explained: 'We are not the place where the politics of security should be discussed but we at the Bank have a problem: we'd rather be apolitical but we don't want to waste your money.'

Promising delegates that the gathering would focus on the next 50 years, the Bank organised seminars and debates under the rubric, 'The Africa we want', ranging from environmental questions and agricultural technology to ways for resource-rich countries to tackle capital flight and sessions on infrastructure.

The Chairwoman of the African Union Commission, Nkozasana Dlamini-Zuma, was clear about what she wanted: 'We want to connect all our capitals with road and rail. Because this is the 21st century, we want it to be high-speed.' On a visit to the AU in Addis Ababa in April, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang had pledged US$10 billion in fresh investment, along with the promise of advanced trains. 'The Chinese say they will site the research and development centre for that project in Africa', added Dlamini-Zuma. Such projects illustrate the AfDB's priorities since Kaberuka took the helm in 2005. Firstly, winning investment from emerging economies to build power stations, roads and railways. The AfDB meetings in Shanghai in 2007, the Bank's first trip to China, put down a marker (AC Vol 48 No 11, The Shanghai set).

A second priority is pushing African economies up the technological ladder to diversify and modernise, expanding processing and manufacturing. The AfDB has energetically brought international development experts to its client states, especially from South Africa and Asia. Tao Yitao, Vice-Party Secretary of Shenzhen University, which was home to China's great economic experiment of the 1980s, spoke at a special session on Special Economic Zones. With François Kanimba, Rwanda's Trade and Industry Minister, sitting beside her, Tao explained the transition from a fully planned economy: 'We learnt from others – a mixture of socialism and capitalism is best for accelerating growth'.

This pluralist approach tallies with the AfDB's. 'We want to offer our members a menu of options, so while we are doing joint research work with the University of Shenzhen, we are also looking at the Brazilian model and others', said Kapil Kapoor, Director of Strategy and Policy at the AfDB. The emphasis on the industrialisation and structural transformation of African economies is relatively new for the Bank, a legacy of Kaberuka's investment in research and development. He established the position of Chief Economist and boosted the research department.

New intellectual outposts are appearing. The latest, the African Natural Resources Centre in Ghana, is chaired by Sheila Khama, a director of De Beers-Botswana and a protégé of Paul Collier, who heads Oxford University's Centre for African Economies in Britain. 'At the end of these ten years in office, I realised that we had to fund our development differently and that we have a chance in a million to use our natural resources', Kaberuka told Africa Confidential. It aims to ensure that Africa uses its natural resources to finance structural transformation. It complements the Bank's African Legal Support Facility, which helps member states to negotiate more effectively with the armies of lawyers and accountants hired by international oil and mining companies.

Recently, the Centre helped Guinea to renegotiate its Simandou contracts,and it worked on the tough negotiations over uranium supply between France's Areva and the Nigerien government, which produced a revised contract this week (AC Vol 55 No 9, Rio's grand suit & Vol 55 No 4, Isolation threatens Issoufou). 'We hire the best international lawyers for these negotiations,' says the head of the Legal Support Facility, Stephen Karangizi, 'with each project costing between $300,000 to $2 mn. in fees.'

Blue economies

Africa is also missing out on the 'blue economy' (maritime economy). South Africa's former Finance Minister, Trevor Manuel, who co-chairs the Global Ocean Commission, pointed out in Kigali that rich countries spend $27 bn. on subsidies for their fishing fleets, many of which end up off the African coast. From his experience in Rwanda, Kaberuka has insisted the Bank and others focus more on war-torn states and those at risk of conflict. He set up a high-level panel to advise the Bank, led by Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, to corral finance and backing from the United Nations, World Bank and European Union.

Money, especially the lack of cash for Africa's infrastructure, remains a key constraint: of the estimated $90 bn. a year needed for new water, power and transport projects, Africa raises about a quarter. So the Bank talks up co-financing plans, leveraging its excellent financial standing to guarantee loans or bring in new funds. One such is the $2 bn. Africa Growing Together Fund, a co-financing deal with China. Pointing to the importance of the initiative, China's Central Bank Governor, Zhou Xiaochuan, flew in for the signing in Kigali and won some knowing smiles for a cautious admission that sometimes the management of Chinese projects in Africa was 'less than satisfactory'. The money will be invested in AfDB projects and subjected to AfDB environmental and social impact assessments.

No procurement preference will be accorded to Chinese companies, insists the AfDB General Counsel, Kalidou Gadio. The money will be spent over ten years: 'We hope this is the first tranche of a facility that will get replenished,' he says. 'There are no strings attached, which must be saluted'. These are Beijing's foreign reserves being put to productive use, said Governor Zhou: 'The Chinese like to save money. We want to put some of those savings to help African development'. The reserves will also earn more in Africa than they do in United States Treasury bills. Similarly, the Bank's Africa50 Fund will use $3bn. in equity investment from the AfDB to draw in African pension funds to finance roads and power stations. Currently, there is over $150 bn. in African pension funds and about $1,000 bn. in Africa's foreign reserves but almost all is invested in Western markets.

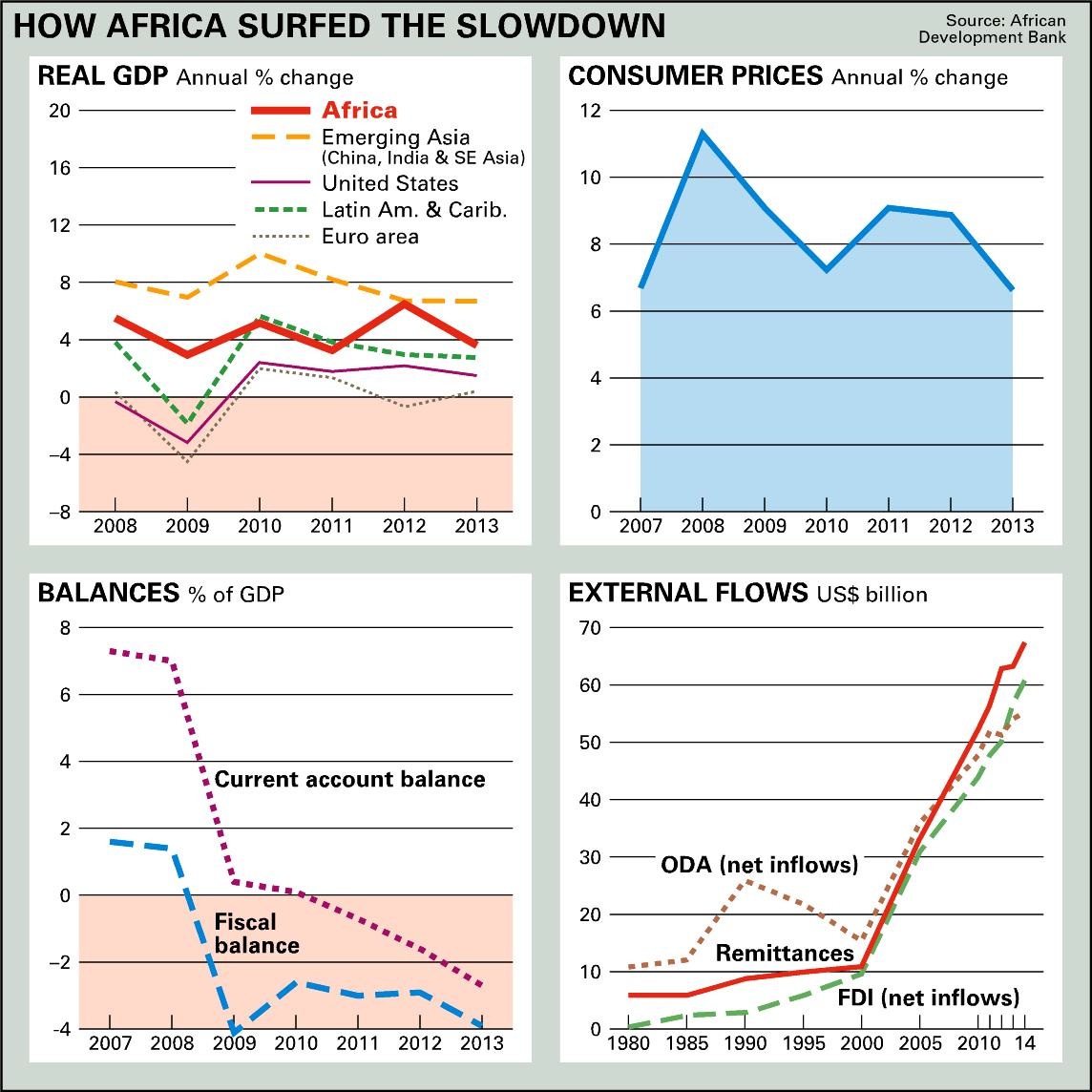

This is changing slowly. In Nigeria, the AfDB has persuaded local pension funds to sign up to an infrastructure investment plan. Currently, Africa invests just 4% of its gross domestic product in infrastructure, versus China's 14%. Backing the idea is Thabo Mbeki, South Africa's former President, who attempted the same with the Pan-African Infrastructure Development Fund in 2007 but was then thwarted by the financial crisis. Then, as Lehman Brothers collapsed in New York and financial shocks rippled across Africa, the Bank helped to shore up several African treasuries in 2008-09. It doubled its loans and grants and tripled the capital base of the AfDB to $100 bn. to meet African financing needs, while Western economies went into recession.

Ballooning costs

Although much has gone right at the Bank, behind the scenes there are mutterings of frustration. Despite a gleaming financial presentation which emphasised its AAA status and risk-management structures, a couple of senior officials complained that the the high command had realised in late April that costs were ballooning and risked outstripping income in November. 'It has been like watching a meteor slowly coming towards us – we have known about it for several years but done nothing', says a senior AfDB official. The result is a slash-and-burn budgetary exercise that will create a headache for the Bank's next President. The official talked of battles between technocrats and sycophants, 'particularly fights about staff who have been appointed in Kaberuka's second term who are just not competent'.

Administrative expenses have almost doubled, from 63 mn. units of account (US$97 mn.) to UA111 mn. between 2009 and 2013. Other expenses have tracked a similar path, from UA69 mn. to UA123 mn. over the same period. Provision for impairment on loan principal and charges – essentially the insurance policy the Bank gives itself on loans its fears it may go sour – has quadrupled from UA11 mn. in 2009 to UA41 mn. Those decisions are the responsibility of the credit committees, which are supposed to be the engine room of good governance. Some of the problems may be a legacy of the Bank's laudable decentralisation, others because of the problems in assessing political risk.

The return to the headquarters in Abidjan also explains some of the overspending. We hear that some urged Kaberuka to postpone the move until the Bank's finances were in better shape but he wanted to take the financial hit is his own term, giving his successor a clean break.

Africa's resilience tested by China's slowdown

Africa's economy has successfully negotiated a tricky 2013, with its major economic partner, Europe, still stuck in recovery mode. For the African Development Bank's Chief Economist, Mthuli Ncube, 'the outlook is still robust for the next few years, North Africa is growing this year at 3.1% while Sub-Saharan Africa will be near 7%, strongest in the west followed by the east' (AC Vol 51 No 12, Bringing in the money).

The reason is partly robust domestic demand, including the somewhat contentious argument about an emerging middle class, and better macroeconomic management, combined with the continued strength of raw materials. 'The commodity super-cycle is different this time, we don't expect prices to collapse that easily', says Ncube, citing the structural shift in global demand with the emergence of large economies such as China and Brazil, and also several medium-sized economies, such as Mexico and Malaysia. This hypothesis is set to be tested by a sharp contraction in China, whose demand for African raw materials has up till now played a useful buffering role in sustaining commodity prices.

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2024

https://www.africa-confidential.com:1070

Prepared for Free Article on 22/11/2024 at 13:14. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.