PREVIEW

After a grilling by bank governors, President Adesina wins backing to open talks on a capital increase

On the morning of 24 May, the universe of the African Development Bank shrank to a single room of the cavernous BEXPO exposition hall in Busan, South Korea's second city, where bankers, African finance ministers and bank governors had gathered for the bank's 53rd Annual Meeting. The main item on the agenda for the closed meeting that morning was whether the shareholders of the bank would agree to increase the bank's capitalisation.

The proposed General Capital Increase, which has been on the Bank's wishlist for several years, has become a defining issue for AfDB President Akinwumi Adesina, with insiders seeing it as an informal referendum on his leadership (AC Vol 58 No 12, Bow ties, flashing smiles and the big sell). Adesina wants the Bank to dramatically increase its workload. 'Africa can't become a museum of poverty', he told delegates.

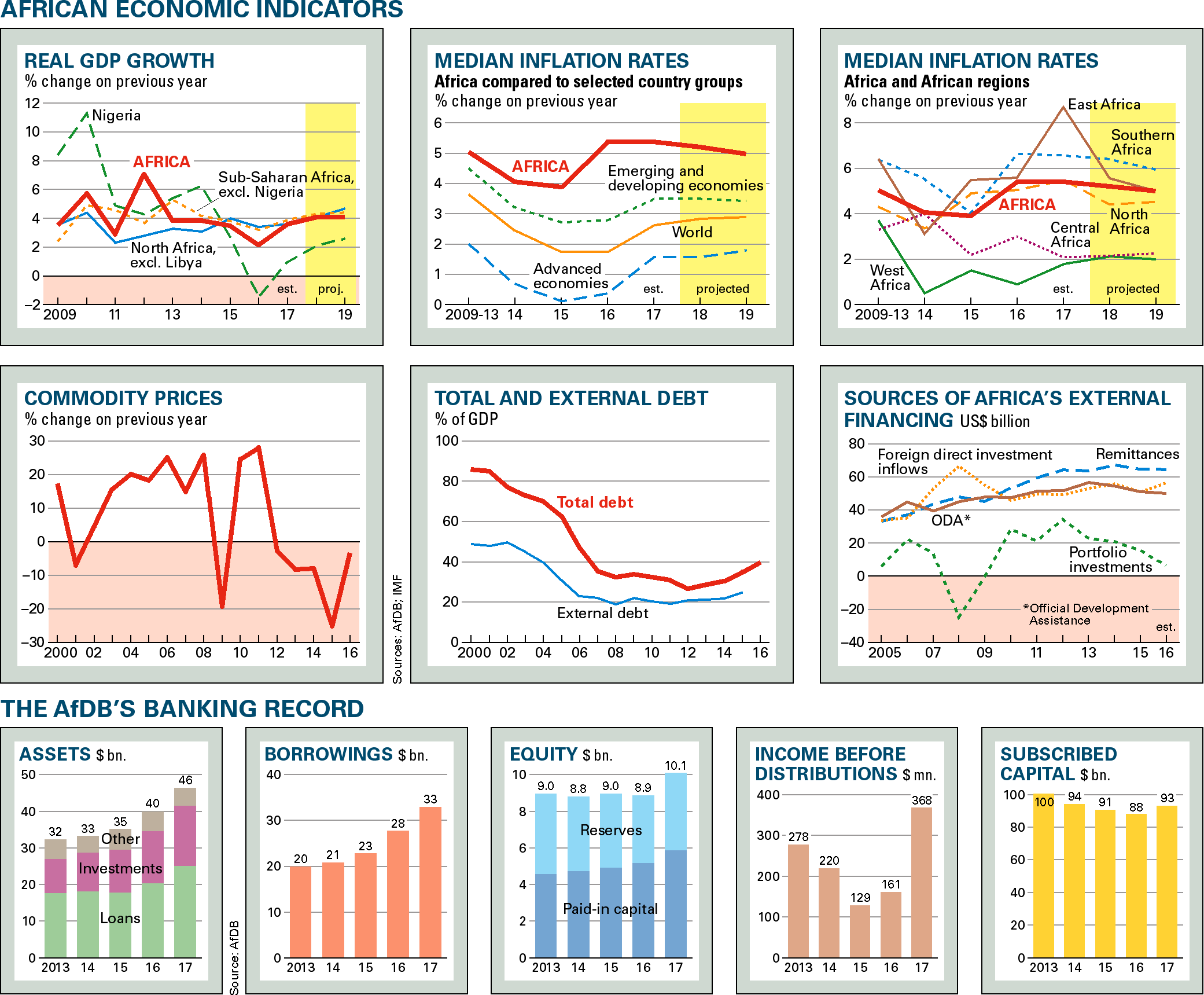

Credit ratings agencies believe that the absence of a GCI would 'raise questions' about how responsibly the Bank treats other people's capital – the Bank is reaching the limits of how much it can lend without triggering prudential concerns (see graph). That in turn could put its cherished AAA rating under threat.

For now, Adesina, the former agriculture minister of Nigeria, retains the support of African governors, who share with him the sense of urgency about Africa's flagging economic development. The markets still see the Bank as a good bet: a recent three-year bond for US$2 billion was comfortably oversubscribed, with a 2.625% coupon. Some financial engineering to securitise the balance sheet may also provide extra headroom for borrowing.

But the 'non-regional' (i.e. not African) shareholders of the Bank – who hold 40% of the capital – are less convinced. Berated by African shareholders who describe the Bank as a 'family' which needs to pull together, the United States governor replied, 'yes, it's a family, but like in every family, you have to do your chores'.

The core complaint is that the Bank wants to ramp up lending without beefing up internal safeguards. The huge jump in disbursements – which hit a record $7.8 bn. in 2017, 15% more than the previous year – has made some governors uncomfortable.

Ruffled feathers

Adesina's abrasive management style and a difficult internal restructuring have ruffled feathers, not to mention his propensity for announcing big lending commitments without approval from the board. A case in point was $1 bn. promised to help Nigeria in 2015 during his first months as President. 'To save face [the governors] gave him $600 mn.', says one bank insider. 'But they never released the second tranche.'

Key posts in the bank remain unfilled after a purge of Vice-Presidents over the last 18 months. The institution also lacks high-level accountability officers, which non-regional governors say must be addressed before any capital increase can be entertained.

Also, there are not enough technical loan officers. That is especially important for private sector lending, which the Bank wants to accelerate.

'There is no running away from helping the private sector. Previously, the Bank's lending to the private sector ran at 10%. Now we are doing 25% [a jump that has happened over the last two years]', says Mukhtar Abdu, the new director of Industrial and Trade Development at the Bank. He recognises that his department currently lacks the capacity to monitor and manage corporate sector loans. 'But I have more than doubled the number of investment officers on my team, these are the workhorses who will do the detailed analysis and financial modelling to make it a decent project. [We will be] bringing in another 100 to 200 of these non-sovereign officers.'

It is easy to see why governors fret about the strength of the Chinese walls between management and shareholders. Take the case of the loan of $100 mn. to the Dangote Group for its Nigerian fertiliser plant announced in May. Mukhtar Abdu was the Dangote Group's head of strategy before he joined the bank in August 2017. The loan was originally approved in 2015, during the bank presidency of Donald Kaberuka, and should have fallen foul of an internal bank rule that AfDB loans lapse 200 days after approval if they are not drawn down.

The Bank is keen to create a new class of 'African champions'. Mukhtar says the Bank is in talks with companies like Shoprite, the South African retailer, and Econet Wireless, the Zimbabwean telecoms provider.

Adesina has also done the Bank a favour by forcing the issue of industrial policy and the role of the state back onto the table, says former Nigerian Central Bank Governor Lamido Sanusi. This is particularly important in critical but neglected sectors of the economy such as agriculture, and a reason why Africa has yet to see a move from raw commodity exports towards more value-added production and industrialisation.

'Between 2012 and 2018, Africa's industrial value-added declined from $702 bn. to $630 bn.,' says Adesina, who points to the demographic wave breaking over the continent. Only three million formal sector jobs are created annually on the continent, while 10-12 million young people enter the job market. Manufacturing has clear potential to employ otherwise idle hands in the Sahel and elsewhere. Ethiopia is often cited as an example of what can be done, with its network of industrial parks, railways and dams.

Risks and rewards

But as Nigeria's Ajaokuta's steel mill readies itself to launch production nearly 40 years and $8 bn. after the project began, the dangers of 'picking winners' are clear. Insiders at the Bank suggest that Adesina may have more success if he acknowledges the risks as well as the rewards.

The Korean-born World Bank president Jim Yong Kim, who shared a stage at the opening session with Rwanda's Prime Minister Edouard Ngirente and his Moroccan counterpart Saad Eddine al Othmani, was keen to stress that industrial policy was only one of several factors that drove South Korea's economic success. Education, including a double shift system in schools, was just as important, said Kim, before delivering an endorsement of Adesina's reforms to the conference.

The relentless pace of investment from China in industrial robots also means that there is no safe haven for factory jobs, either, putting any industrial policy on to a very tight time leash. Al Othmani says, '60% of jobs will disappear over the next 10-20 years… So, we will need to train for the jobs of tomorrow, not just shoot at the jobs of yesterday.'

That requires the kind of economic planning skills – and disciplined leadership – that few African countries currently have. 'Subordinating finance to industrial needs is a bet, and the risks are much bigger', says Admassu Tadesse of the Trade and Development Bank, the financial arm of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). 'Can you build a developmental state to reward performance?'

That question cuts to the heart of criticism of the route Adesina has chosen. For while South Korea and Japan and other countries who have successfully tried state-led development embedded market mechanisms into their subsidies – tying cheap credit to export performance, for example – this is a point that the AfDB is quiet on.

Tax matters

There are other things countries need to be encouraged to do to raise capital first, suggests Sanusi. While he agrees on the need for industrial policy, there are other ways to raise cash before hitting the capital markets. One is the tax base; both the tens of billions lost to tax fiddles by foreign multinationals and increasing domestic tax revenue. But 'corruption is the elephant in the room', he says. 'There is a clear correlation between the ability to develop and the level of transparency.'

Without this rigour, the debates over the direction in which Adesina has pointed the bank will rumble on and into the capital increase negotiations.

Only one governor – the US representative – voted against the motion to launch official AfDB consultations over a GCI. These are likely to start in October and Adesina wants them to take a year, providing him with a neat fillip as he heads into his re-election campaign.

The decision to bring back Victor Oladokun as communications director, a veteran of his previous campaigns, is one sign that Adesina will run again. So, too, was the attempt to patch things up with other rivals, such as Frannie Leautier, the senior VP who left the Bank in unhappy circumstances last year. Her presence – she is rumoured to be eyeing up Adesina's chair – did not go unnoticed in Busan.

Other candidates are also warming up their pre-campaigns. World Bank Africa region president Makhtar Diop has found a new job as World Bank infrastructure Vice-President, to keep the resumé warm (AC Vol 55 No 7, Hitch for dam plan). Rumour has it that since the donors decided to replenish the World Bank's International Development Assistance in 2016 at the expense of the AfDB, all Adesina's pleas to donors for more capital find him re-directed to Diop, much to his irritation.

Next year will see Equatorial Guinea host the meetings. Malabo may be neither developmental state nor fiscal disciplinarian but it is no stranger to plots to unseat leaders.

Economies need reform, and reform means tax

The African continent is recovering quickly from the commodity-price trough as prices for crude and cobalt improve. But inflation has shot up, with a median rate of 5.4% across Africa, well above comparator regions. Debt levels have crept up, while currency reserves are far from replenished. Commodity prices are weak, and infrastructure projects, bought in dollars, are being paid for in vulnerable local currencies. The US federal reserve rates are creeping up, meanwhile, pushing up the cost of capital.

And while growth is back – Africa as a whole hit 3.6% in 2017, with 2018 estimates at 4.1% – per capita growth is stagnant when the rate of demographic growth is factored in. East and North Africa lead the pack in terms of growth rates, with Central Africa lagging behind.

The overall picture has been boosted by the recovery of the continent's two economic giants from largely self-inflicted wounds; Nigeria's costly defence of its currency, and South Africa's expensive dalliance with the Gupta family.

Traditionally, such turnarounds in fortunes often come when resource-rich countries ditch their onerous plans for diversification, and bathe in rents from oil and minerals.

For AfDB economic planners, the need for Africa to deepen its tax take is the only long-term solution to drive structural reform of its economies. Estimates of the amount the continent loses in capital flight through transfer-pricing and other multinational tax dodges now put it well above $50 billion – double the amount it receives in aid.

There is also a large domestic tax base that remains untroubled by the tax collector and which could yield significant sums. The average tax take to GDP ratio in sub-Saharan Africa is 17%, and just 6% in Nigeria, 'below the 25% threshold deemed sufficient to scale up infrastructure spending', according to the recently released African Economic Outlook.

For former Nigerian Central Bank Governor Lamido Sanusi, this is significant for the latest discussions on Africa's debt sustainability. He complains that the 'farcical' debt-to-GDP ratio should not be the most popular data point when considering how viable a nation's debt burden has become, 'because you service a debt from revenue, not GDP, and if only 6% of your country is paying taxes then it's irrelevant'.

Debt itself is changing in nature, with private debt contracted by governments the latest iceberg to threaten the continent's progress. Zambia and Mozambique exemplify the dangers of debt contracted from private banks at usurious rates for non-productive assets (AC Vol 59 No 10, A swirling fog of debt). But there are more subtle cuts. Kenya, for example, has overpaid for its new rail infrastructure, erasing much of the gains the economy will receive (AC Vol 55 No 4, No way to run a railway).

|

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2024

https://www.africa-confidential.com:1070

Prepared for Free Article on 22/11/2024 at 18:19. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.