PREVIEW

The radical nationalists and Islamists helping the army defeat the Rapid Support Forces in Khartoum will haunt the new regime

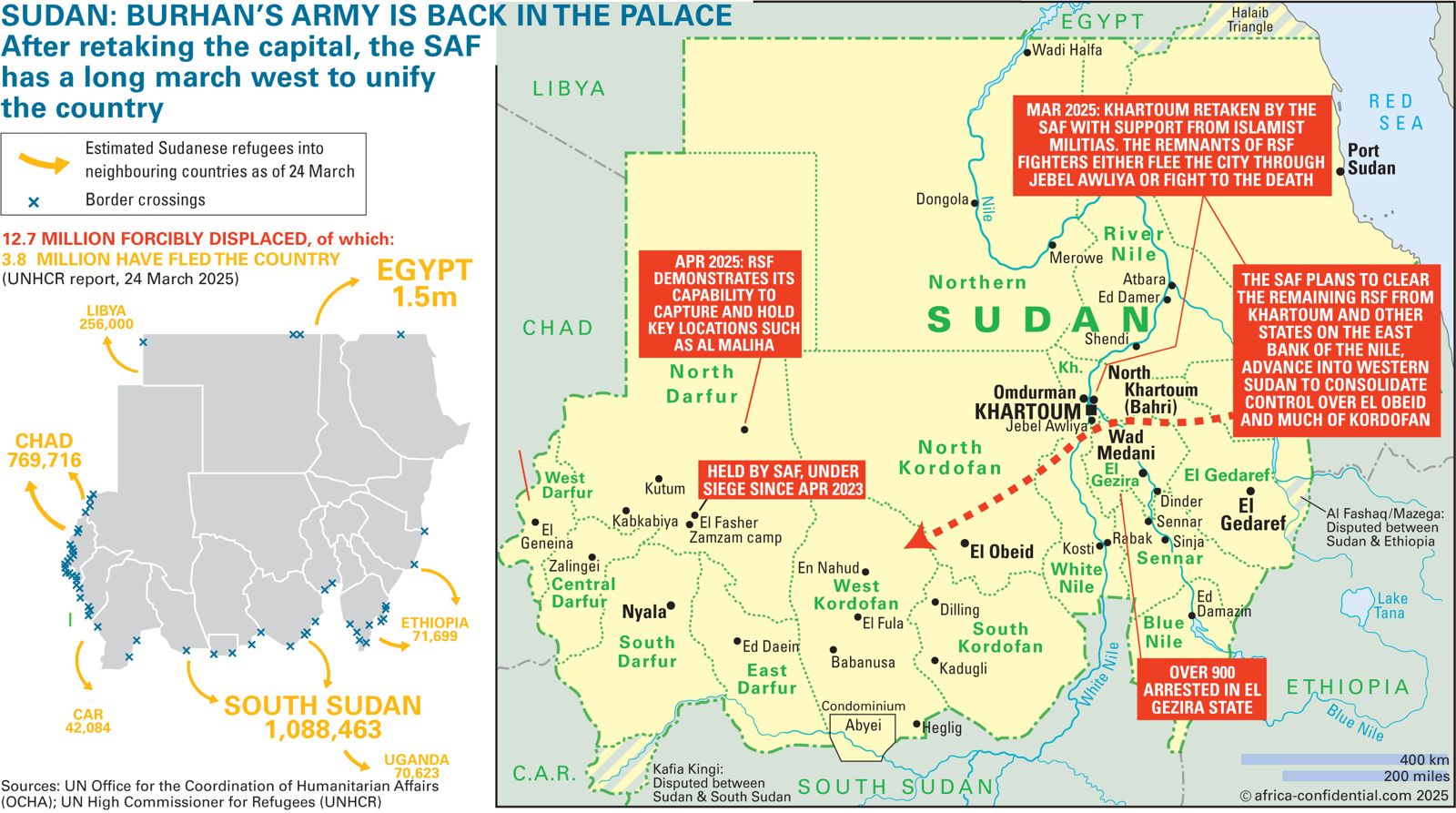

On 15 April 2025, General Abdel Fattah al Burhan will commemorate two years of war against the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) from the presidential palace in Khartoum. As remnants of RSF fighters either flee the city through Jebel Awliya or fight to the death, they remain encircled by Burhan’s Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and its allied militias.

The SAF’s recapture of the capital marks both a symbolic and strategic triumph. It reinforces Burhan’s junta as a legitimate authority, with recognition from the United Nations. And it delivers a decisive blow to Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo Hemeti’s attempt to establish a rival government backed by the United Arab Emirates (AC Vol 66 No 4, The generals choose partition over peace & Dispatches 24/3/25, Burhan’s forces capture presidential palace, tightening their grip on Khartoum).

When the RSF held its public meeting in Nairobi on 22 February, it presented a new constitution declaring Sudan a ‘secular, democratic, decentralized state based on the separation of religion and state, and equal citizenship as the basis for rights and duties’.

It wants to win regional and international support to oppose the return of Islamists to power in Sudan under Burhan, railing against a revival of the National Islamic Front (NIF) regime in Khartoum that ruled from 1989 until its overthrow in 2019 (AC Vol 66 No 5, Hemeti struggles to launch in Nairobi, again).

Following the SAF’s recapture of Khartoum last month, business leaders and regional officials are talking Burhan about financing the capital’s reconstruction. Yet the transition envisioned after the 20 February constitutional amendments faces many roadblocks. These amendments grant the SAF control for 39 months before elections transfer power to civilians. Key issues include managing liberated areas east of the Nile, continuing the offensive to reclaim Darfur, and engaging with international partners.

Militia manpower

The SAF’s triumph in Khartoum relied heavily on support from militias tied to the old regime, the Islamists, and the former ruling NIF and National Congress Party (NCP). In late 2024, the Al Baraa Ibn Malik Battalion changed its name to Brigade, reflecting its expansion to over 15,000 members. This group fills the SAF’s long-standing infantry gap and is equipped to deploy drones and artillery.

No one knows whether the political rifts between the SAF and militia groups can be contained. Burhan, unlike Beshir, is not a staunch Islamist and may fear that Islamist factions in Khartoum could limit his political aspirations. Some may target Burhan for ordering Beshir’s arrest in the wake of the April 2019 revolution. The relationship between the SAF’s officer corps and Islamist fighters is often intentionally opaque.

It’s unclear whether Islamist militias will prioritise their military role alongside the SAF in retaking western Sudan and Darfur or concentrate on a more overtly political role in reconstructing and consolidating Khartoum’s state apparatus. So far, Islamists have focused on gaining control over the judiciary, administrative and diplomatic appointments, while preparing for the political transition. They have prioritised releasing jailed NCP cadres and unfreezing assets of banned Islamist front companies which amount to hundreds of millions of US dollars.

Debilitating tensions between the Islamists and the officers may take time to surface. As substantial funds flow into Khartoum and the rainy season restricts military operations, attention will shift to informal power-sharing deals in Khartoum.

Islamist militias have been the most aggressive in targeting those suspected of collaborating with the RSF. Over 900 people have been arrested and detained in El Gezira State. Many in Khartoum fear that people from the Nuba Mountains and South Sudan could be labelled as RSF supporters and shot dead on sight. That also applies to activists involved in the 2019 revolution against the Islamists and Beshir’s regime. Journalists and civil society workers are also likely targets.

Western advance

Senior SAF officers are planning the next phase of the war. They want to clear the residual RSF fighters from Khartoum and other states on the east bank of the Nile. Then they plan to advance into western Sudan to consolidate control over El Obeid and much of Kordofan, and launch military operations in South Darfur while bolstering the Sixth Infantry Division and joint forces in North Darfur.

Those plans may face serious obstructions. Security in ‘liberated areas’ is weaker than anticipated, requiring the deployment of more troops and militias to ease the return of displaced populations and secure supply lines.

This highlights the geographic variation in attitudes to the SAF. The territory seized from the RSF is either supportive of the army or, more likely, fundamentally hostile to the RSF for several reasons, including ethnic prejudice against RSF fighters from Darfur.

But this hostility carries less weight as the SAF and allied militias advance westwards to Darfur. Community allegiances are highly polarised, making it harder for the SAF to identify allies. All this may slow down or derail the SAF’s military operations.

In recent few weeks, the SAF has reorganised contingents that fled to South Sudan from South Darfur and remained near the border in 2024. They may now see an opportunity to reorganise these contingents into a military force able to target gold mines controlled by the RSF and its allies – potentially heightening divisions among communities or leaders who have differing views on the RSF and Hemeti.

Over the past year, the Baggara and Rizeigat ethnic groups have clashed repeatedly. Among the Rizeigat, tensions between the Mahamid and Mahariya clans, driven by tribal and political ambitions, are embodied in the long-standing hostility between Musa Hilal, a Mahamid leader and former Janjaweed militia chief, and Hemeti, who belongs to Mahariya (AC Vol 63 No 19, Junta's double-talk on transition).

Developing a political solution would require time and foresight. Both are scarce after two years of devastating war. Defending North Darfur is still trickier. Strengthening the Joint Forces, primarily the Zaghawa armed groups, appears rational and necessary.

Yet the RSF is still showing its capacity to capture and hold key locations such as Al Maliha. The city, a stronghold for the SAF and Joint Forces, is a strategic crossroads connecting Al Dabbah to the north, Hamrat al Sheikh in North Kordofan to the east, and El Fasher to the south. The RSF, arriving with some 700 combat vehicles, seized the town and retained control. This is despite Joint Forces being reinforced from outside.

The Meidob community reported dozens of its members were killed by the RSF.

Should the SAF grant more credibility to Minni Arkou Minnawi, leader of a faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement, and other Zaghawa commanders, it could prompt demands for power-sharing beyond Darfur. It may also strain relations with Chad and its president, Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno ‘Kaka’ (AC Vol 66 No 7, Mahamat Kaka is caught between Khartoum’s anger and Emirati cash).

KHARTOUM’S SUITORS JOSTLE FOR PRIMACY

Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) Commander General Abdel Fattah al Burhan has to clarify his line on regional and international relations. His offensive has returned many areas, including the capital, to SAF control – but it has relied heavily on arms and logistics from Russia, Iran, Egypt, Turkey and Qatar. Managing such a disparate support base while maintaining access to western finance will demand diplomatic finesse, not his strongest suit (AC Vol 66 No 1, Region will be key in bid to end war).

A delegation from Saudi Arabia visited on 27 March, sending a strong signal and was taken seriously by Sudanese military officers. Led by Saudi Ambassador Ali bin Hassan Jafar, it pledged humanitarian aid, plans to rebuild the capital, and macroeconomic support for a currency much weakened by the war.

Riyadh differentiates itself from Abu Dhabi’s opposition to Islamists and support for the RSF. It wants to stop Khartoum’s regime from becoming either a civilian democracy or an Emirati puppet. Those priorities are shared by Burhan and his circle.

To strengthen its position, Saudi Arabia may propose a diplomatic initiative that risks antagonising UAE President Mohammed bin Zayed al Nahayan (MBZ). It may also offer the United States a role that maintains Washington’s relevance without direct commitments.

The attempts to form an Africa team in President Donald Trump’s administration in the United States have stalled. Air Force Colonel Jean-Philippe Peltier has declined to take Africa Director in the National Security Council role, ostensibly but improbably due to a dispute over accommodation.

The conference on Sudan, organised by Britain in mid-April, might offer a platform for a Saudi-US-European initiative. Riyadh recognises the interest of several US lawmakers, including Representative Sara Jacobs, Senator Chris van Hollen and Representative Gregory Meeks, who have openly criticised the UAE’s arming of the RSF. Saudi officials may collaborate with them to counter the visit of UAE National Security Advisor and Abu Dhabi Deputy Ruler, Tahnoon bin Zayed al Nahayan, whose surreal investment plans of US$1.4 trillion over the next decade have raised eyebrows, even by Emirati standards.

MBZ shares Trump’s transactional, zero-sum approach to politics. His endorsement of the Abraham Accords stands as Trump’s key Middle East foreign policy achievement, supported by a well-funded and effective lobbying network in Washington. Yet MBZ’s Sudan ambition is becoming a deadly liability. His plans for Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo ‘Hemeti’, a protégé with strong commercial ties to Abu Dhabi, to lead Sudan have been derailed, marking an expensive, in terms of blood and treasure, failure in Africa. Public discourse and social media reveal that the UAE’s heavy backing for Hemeti’s military and gold smuggling operations has damaged Abu Dhabi’s reputation, seen increasingly in the region as a cash register whose diplomatic line is as unreliable as any western power.

|

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2025

https://www.africa-confidential.com

Prepared for Free Article on 24/04/2025 at 20:28. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.