PREVIEW

Recoveries in Africa and South Asia are lagging behind industrial economies in what the IMF calls a dangerous divergence

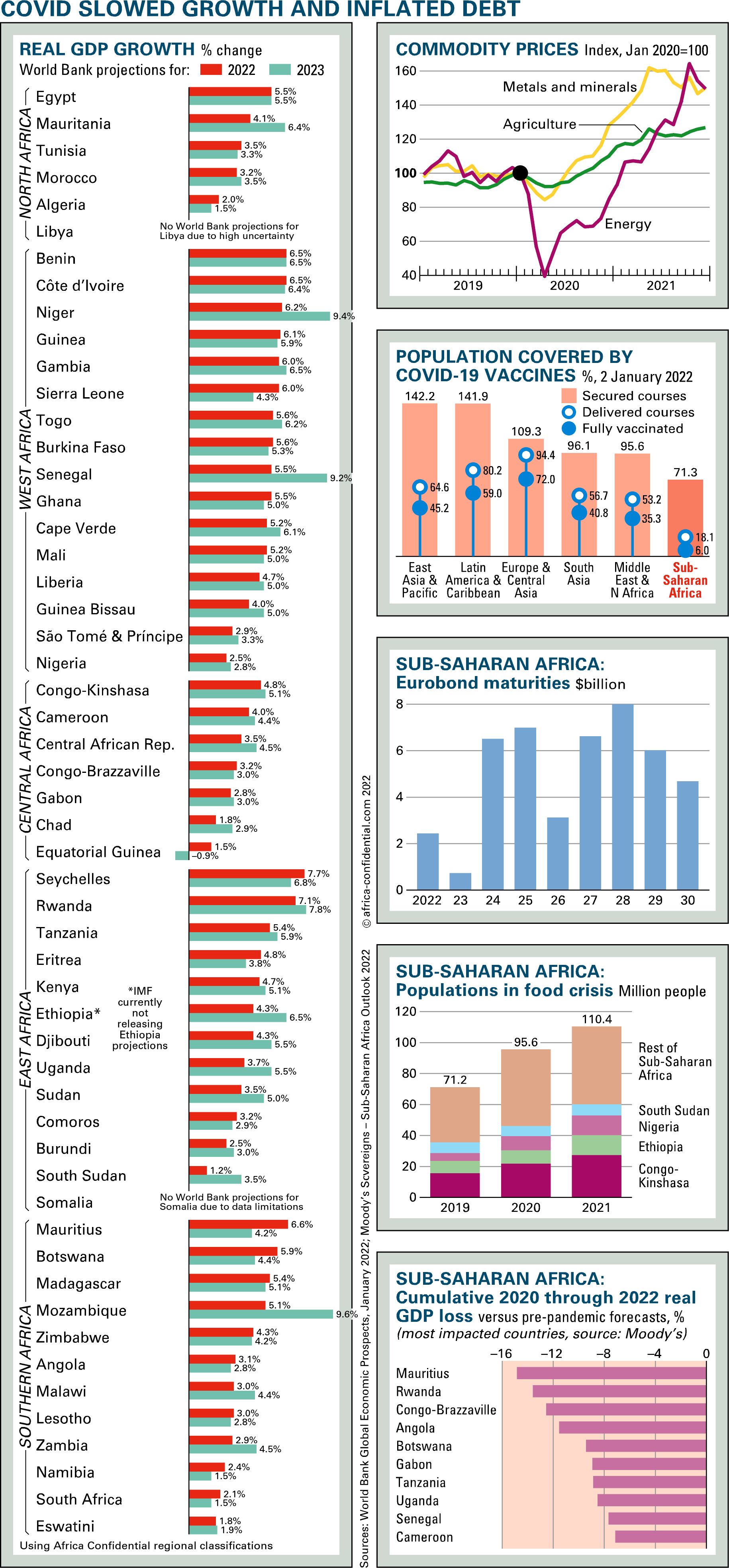

Several African economies could still take years to recover from the loss in GDP suffered from the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, according to the latest World Bank data.

The World Bank now estimates that sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) will enter 2023 with GDP 4% below where it had been forecast to reach in pre-pandemic estimates. That is worse than all developing regions except South Asia, and in stark contrast to advanced economies on course to return to pre-pandemic trends by next year.

Ratings agency Moody's calculates that the worst-hit African economies could, by end-2022, have registered even greater cumulative losses in output. In some cases, these losses amount to 10% or more of GDP when compared to the pre-pandemic forecasts.

Latest projections from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank suggest overall SSA real GDP growth should meet or exceed 3.6% this year. This level of growth is forecast even without the benefit of significant 'base-effects' that pushed up 2021 growth to around 4%, when several of the region's economies partly recovered from their Covid-driven 2020 contractions.

Along with those in South Asia, Africa's economies have been the hardest hit by the global pandemic. The danger in Africa comes not just from faltering growth, but also from the political reaction to the toll of hardship.

Initially, the momentum from Africa's growth surge in the early 2000s had carried many economies into an era of reform and restructuring. By 2010 many economies resumed a growth path, helped by a global commodities boom. New technologies, digitisation and renewable energy were driving change, but not yet on the required scale.

In many areas, such as the coastal economies of West Africa, the Indian Ocean seaboard in East Africa, and Morocco with its state-led industrialisation, the new economic policies were succeeding. In other cases, grand industrial projects were not enough to make a significant impact on growth – examples being Aliko Dangote's gargantuan oil refinery, fertiliser and petrochemical plant in Nigeria, and the Ethiopian government's agro-processing schemes (AC Vol 62 No 17, Energy law unsettles rentiers).

The economic planners also have to contend with security crises. Insurgencies in northern Nigeria and civil war in Ethiopia are putting the federal systems in both countries under serious strain (AC Vol 63 No 2, After concessions, rival armies fight on).

Voter verdict

In August, voters in Angola and Kenya, both countries hit by rising debt service burdens and slowing growth, will cast their verdict on the performance of the João Lourenço and Uhuru Kenyatta governments (AC Vol 63 No 1, The opposition sees a new chance). In both countries, opposition politicians hope to capitalise on social discontent and can look towards Zambia as an example of what they could achieve. Last year, Zambians overwhelmingly voted out Edgar Lungu's Patriotic Front government, primarily because of economic mismanagement and galloping corruption.

In South Africa, the African National Congress has seen its share of the vote shrink, due in large part to anger over corruption. In neighbouring Zimbabwe, where conditions are far worse, the ruling party has kept its grip on power through ruthless repression and tearing apart the opposition.

In the countries of the Sahel, organised criminal gangs and Islamist insurgents are stealing resources and preying on local communities, exploiting their grievances against economic injustices.

In Sudan, in the wake of the generals' coup last October, resistance committees are confronting the regime on the streets, week after week. The crashing economy means the opposition is widely supported, despite the junta's use of deadly force to break up protests.

Latest World Bank figures suggest that by the end of last year, almost 110 million in sub-Saharan Africa were experiencing 'food crisis'. Average inflation in the region, although varying considerably between countries, is predicted by the IMF to return to single digits this year. Yet prices remain vulnerable to unpredictable events, whether related to African security or global developments impacting oil and gas prices.

Pushback

Standard Chartered's chief Africa economist Razia Khan warns of 'social pushback', where proposed government measures to increase taxes and eliminate subsidies – the latter typically being among the reforms urged on governments by the World Bank and IMF – provoke domestic opposition.

In Nigeria, plans to end fuel subsidies now look likely to be shelved until after next year's general elections. In Ghana, a controversial levy on electronic transactions has sparked parliamentary protest and a walkout from opposition politicians (AC Vol 62 No 24, Bonds and budget blockers).

Moody's predicts only a modest improvement in average sub-Saharan Africa fiscal deficits, from 5.2% in 2021 to 4.5% this year, in the face of competing social demands from those at the sharp end of Covid-driven increases in poverty.

The growth rates of key African oil producers Nigeria and Angola are set to lag behind the African average, at around 2.5% and 3% respectively, according to the World Bank. Africa's most populous nation could grow more slowly than any of the other 15 smaller economies in the West Africa region, even if likely growing faster than sluggish South Africa and oil exporters Chad and Equatorial Guinea.

Yet oil prices north of $80/barrel, combined with gradually increasing crude oil output from the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies (known as OPEC+), could boost revenues and spur on oil sector investments in Nigeria and other oil- and gas-producing nations.

African officials oppose the push for a 'zero-carbon' policy, which would hamper oil and gas projects in Nigeria, Mozambique and elsewhere that African policymakers laud as key for development. This opposition will surely persist, even during a year when the COP27 climate summit is scheduled to be held in Egypt. In fact, Egypt's economy could significantly exceed 5% growth this year, thanks in part to an expanding gas sector.

A number of non-resource-intensive economies, and economies dependent on tourism, could see relatively strong 2022 growth, despite the potential impact of high commodity prices on the formers' fiscal balances and the risks to international travel posed by Omicron or another major Covid variant. Likewise, some agricultural commodity producers (including increasingly-indebted Kenya and Tanzania) could see growth of around 5%.

Conflict continues to be a major growth disruptor, whether in the Sahel region or elsewhere. Due to its Tigray conflict, the IMF now declines to release growth figures for Ethiopia, which averaged around 9% annual growth from 2010 to 2019.

The slow pace of African Covid vaccinations, which lags other developing regions, reflects the low capacity to administer the vaccine as much as Africa's shortfall of doses. IMF economists are now calling for an extra $23.4bn in financing for the World Health Organization's Access to Covid-19 tools Accelerator, for vaccination campaigns and medical infrastructure in developing countries. But Africa's relatively low death rate from recent Covid variants could indicate it will be protected from the worst Covid scenarios.

Africa faces finance squeeze as US rates rise

Africa economies seeking to borrow on the international markets could be in difficulty if the US federal reserve rates are increased more than anticipated.

Greater-than-anticipated US federal reserve hikes could prompt significant capital outflows, and put pressure on central banks to increase the price of domestic credit, potentially dampening growth. Although Nigeria and Ghana have held rates this month, and Covid-era Africa rates cuts significantly outnumber hikes, South Africa's reserve bank now tends to take its cue on interest rates from the likely direction of the Fed.

On the plus side, some African economies should be able to dedicate part of last year's Special Drawing Rights receipts towards financing their 2022 budgets, and further concessional financing remains an option for a portion of Africa borrowings (AC Vol 62 No 16). But many economies remain at high risk of – or are currently in – debt distress, and there is considerable uncertainty over how ongoing debt negotiations will play out, whether or not under the G20's Common Framework in which Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia are participating.

Recent calls by IMF deputy managing director Gita Gopinath for the Common Framework to be 're-vamped' for speedier debt restructuring, and for creditors to suspend debt servicing during these negotiations, illustrate the persisting uncertainty over how the framework will operate (AC Vol 62 No 9, Forecasts fail to lift the gloom). World Bank economists comparing the framework to major historical debt restructurings say that maturity extensions and reduced interest rates are more likely than debt haircuts. They also observe that the framework's requirement for borrowers to obtain 'comparable' debt relief from private sector creditors is ill-specified and without a 'mechanism' to push private sector creditors to play ball.

Citi's chief Africa economist David Cowan takes the view that Zambia's Common Framework negotiations could be resolved within half a year, and that could set the precedent for other African countries. While Zambia's Eurobond holders could accept outright forgiveness of some of debt, he says, it is harder to assess whether Zambia's numerous Chinese lenders – including China Exim Bank and the China Development Bank – will also do so. Zambia's China lenders may push for private sector status in negotiations where at all possible (AC Vol 63 No 1, Hichilema enjoys a honeymoon).

At November's Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in Senegal, China pledged US$40 billion in financing and investment to Africa over the next three years. Large as this may be in absolute terms, this is a reduction in China's commitments. Another worrying development is the ongoing fallout from China's property market from the Evergrande crisis, which could hurt commodity prices, and thus also the African borrowers dependent on them.

|

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2025

https://www.africa-confidential.com

Prepared for Free Article on 25/04/2025 at 11:16. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.