PREVIEW

Opposition activists are determined to hold the government to account for a crisis that will see half the country in need of food aid next year

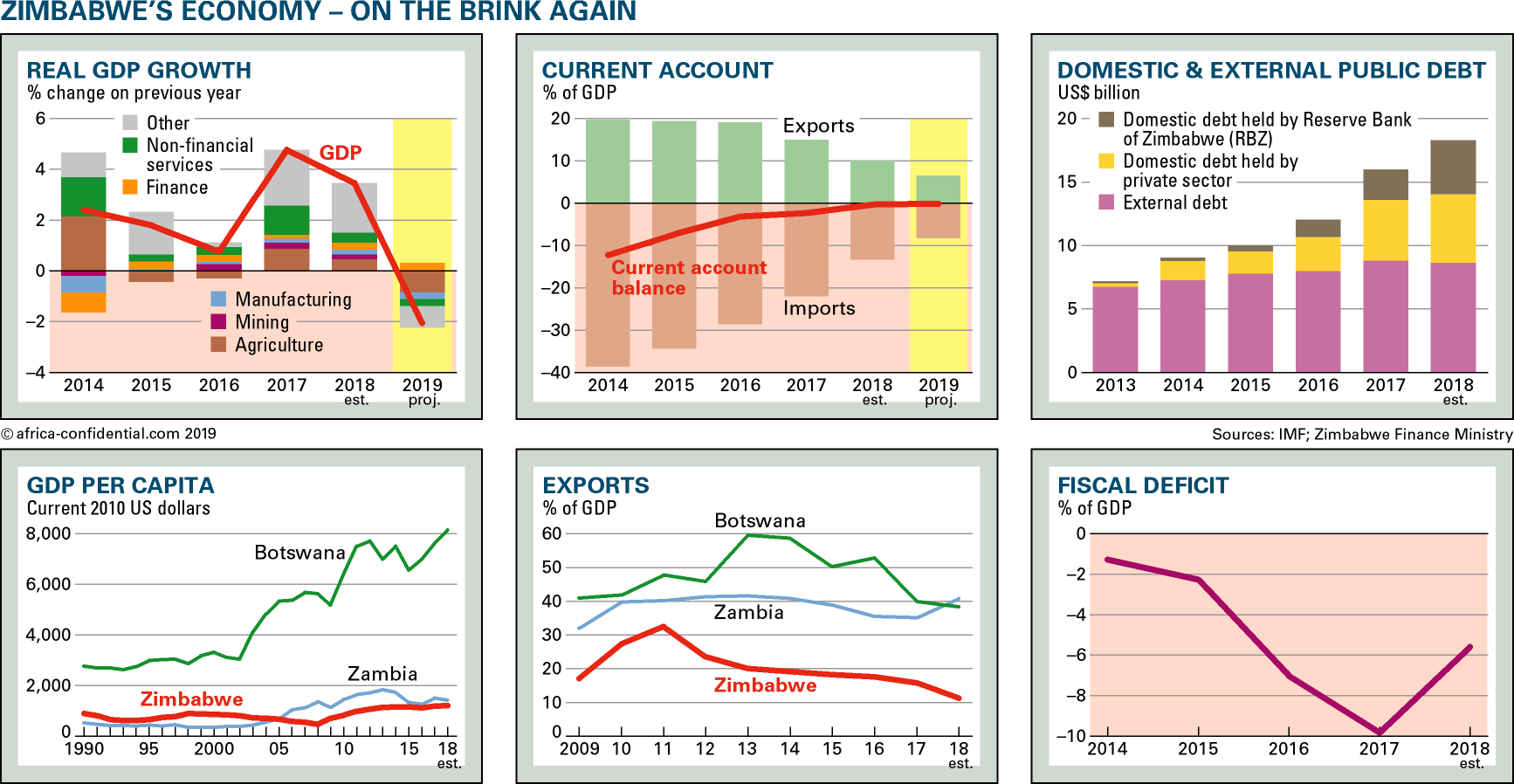

With 8.5 million people facing serious food shortages next year, the discovery that some senior state officials are profiteering by importing 17,000 tonnes of grain at double the world market price is the latest blow to the diminishing credibility of President Emmerson Mnangagwa's government.

Africa Confidential understands that the grain was brought in from Tanzania – Mnangagwa and President John Magufuli are allies – at a price of US$600 a tonne; the world price is currently $240 a tonne. An expert in the regional commodity trade said the only explanation for the inflated price of the consignment is a 'vast corrupt rake-off'. Now the keys question are, says the expert, who knew about the deal and who benefited from it.

Senior officials in international organisations have confirmed the pricing of the deal and say it helps explain the slow response to the United Nations' call for emergency funding to alleviate Zimbabwe's food shortfall. It comes as relations between the government and Western states falter again, after a brief improvement following the ousting of President Robert Mugabe in November 2017 (AC Vol 58 No 25, A martial mind-set).

Although the main cause of the food crisis is the drought which has hit most countries in the region, corruption and mismanagement are making it worse. The World Food Programme (WFP) estimates at least half Zimbabwe's population of 16.5 million are now 'food insecure', a staggering failure in a country that was the breadbasket of southern Africa.

Those at risk in Zimbabwe are not far short of the 9.7m needing food aid in all the 17 countries of the Sahel and West Africa combined.

Nor is Zimbabwe's crisis confined to the rural areas where 5.5m people are food insecure. Another 3m in towns and cities also face chronic shortages. At the start of the crisis it was estimated that it would cost $300-500m to feed 7m people; now another $100m will be needed.

Grain need

Some 800,000 tonnes of wheat and maize may have to be imported to avert disaster. This doesn't include the grain needed to keep farm animals alive: up to half of all cattle could die in some areas. In July, some agency estimates suggested Zimbabwe would need 1.3-1.4m tonnes – 850,000 tonnes of white maize, 350,000 tonnes of wheat and 80,000 tonnes of soya and cooking oil. That includes animal feed.

But trust in the government is low. A WFP 'flash appeal' has so far secured pledges of only about $150m: $89m from the United States, €9 mn ($10m) from the European Union and £50-60m ($60-75m) from the United Kingdom.

If money can be raised for emergency imports, there are still big logistical challenges that increase the risk of starvation. Zimbabwe has enough grain to support its population for the next three months. Drought has affected the whole region, so most imports will have to come from outside Africa.

Even if procurement deals are reached rapidly, it may take two months to move the grain from, say, Mexico to the main import gateway ports – Beira in Mozambique and Durban in South Africa. Beira remains seriously damaged by the recent cyclone, so more shipments will have to come through Durban, which is further away.

This will impose huge pressure on the run-down railway network and on the availability of trucks. If the import needs are as great as 1.3 million tonnes, the railways could probably only move about a tenth leaving the rest to be trucked, at the rates of 4,500 tonnes a day. That would need over 1000 lorries, operating a shuttle for several months.

The government's policy response to food supply has been the Command Agriculture system, a state-backed system providing seeds and fertilisers. Apart from governance and corruption issues (see Box), the programme was compromised from the start because so many land-holding beneficiaries had secured the best farmland through political loyalty (AC Vol 60 No 18, Cash at the generals' command).

In many cases the loyalists lacked the skills and personal commitment to make their farms more productive but were favoured in the distribution of inputs under Command Agriculture. However, tens of thousands of serious farmers did benefit from the contested land redistribution in the 2000s and many have rebuilt production.

But a common complaint is that farmers who are not overtly loyal to the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front face discrimination under the Command Agriculture scheme. Many of those giving Mnangagwa and his allies the benefit of the doubt two years ago now see it as both brutally authoritarian and incompetent, having reneged on its promise to open the economy to legitimate business.

One of the biggest shifts is the government's loss of support from public sector workers. Over the last five years, state sector workers were the main beneficiaries of the state. The average civil servant was paid Zimbabwe$ or RTGS1000 per month ($600-700) in the past three years. They were doing better than most other workers.

Now state workers are underpaid because inflation has massively eroded the real value of their salaries. The average salary of RTGS1000 is now worth only $60-70 in market terms.

Many civil servants are the only regular wage earner in a household of five or six. Now there are cases of civil servants and their families suffering from malnutrition. Beyond the human suffering, this hits their ability to work, further undermining state administration and public services.

This has prompted strikes such as the continuing clashes between doctors and nurses and Mnangagwa's government. The brutal response to these protests is triggering further dissent in the cities where support for the opposition is already strong. Although the opposition has failed to capitalise on this growing anti-government sentiment, the prospects for a wider and more decisive confrontation increase as conditions deteriorate (AC Vol 60 No 17, Activists take on the crisis).

The Sakunda price

Investigations by Parliament's Public Accounts Committee into how the army-backed oil importer, Sakunda Holdings, has profited from the Command Agriculture scheme are causing international problems.

First, is Sakunda's long association with the Amsterdam-based Trafigura oil trading outfit. Sakunda has a stake in Trafigura Zimbabwe; Kudakwashe Tagwirei, Sakunda's chief executive and once close to President Emmerson Mnangagwa, was a key enabler of Trafigura's business in Zimbabwe (AC Vol 59 No 22, Trafigura in a tug-of-war). The joint venture company, Trafigura Zimbabwe, is accused of contributing, directly or indirectly, to Mnangagwa's re-election campaign (AC Vol 58 No 4, ZANU-PF digs for votes).

There is little transparency about Trafigura's links to the Command Agriculture scheme before it became a government-funded programme. The trader denies any wrongdoing in the matter. There is no ambiguity about the role and networks of its local partner, Sakunda.

The second risk is that Sakunda's operations are undermining the onerous economic reform programme pushed by Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube. So close is Sakunda to the government and the Reserve Bank that it has benefited from preferential exchange rates between the local Zimbabwe$ or RTGS and the US$.

The deal uncovered by former Finance Minister Tendai Biti and the Public Accounts Committee allowed Sakunda to receive US$366 million in government bonds as payment for supplying inputs for Command Agriculture.

When Sakunda redeemed some of those bonds at a preferential exchange rate (reckoned to be US$1=new RTGS/Zim$9-10) – everyone else was being repaid on basis of US$1- new RTGS/Zim$1). This led to an 80% surge in money supply.

On 20 February, all contracts were converted from US$ contracts into local contracts: all assets were converted to Zimdollars, including Treasury Bills and other government paper. There was one exception: Sakunda which was allowed to hold onto its bonds denominated in US$.

Sakunda started to unload these bonds in July 2019. But only one bank took the bonds. Most banks lacked the liquidity to do so and their executives were also worried about the legality of doing such a transaction. So Sakunda turned to the Reserve Bank. Sakunda managed to unload $220-230m of the $366m. It retains some $100 million on its books, while a further $20-40m is placed with a local bank.

In the main transaction, the Reserve Bank had in effect created a massive sum of new local dollars, about Zim$2.3 billion, a huge increase in the reserve money. After criticism from bankers and international agencies, the government froze the Sakunda accounts and the company's political network appears to have been hit almost as badly as the local currency.

|

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2025

https://www.africa-confidential.com

Prepared for Free Article on 25/04/2025 at 23:16. Authorized users may download, save, and print articles for their own use, but may not further disseminate these articles in their electronic form without express written permission from Africa Confidential / Asempa Limited. Contact subscriptions@africa-confidential.com.